HISTORY OF THE RHODES PROJECT

By Dr Ann Olivarius

The idea behind The Rhodes Project was planted in 1977 when I found myself surrounded by a New Jersey snowfall and nervous conversation during the evening cocktail reception that traditionally kicks off the final round of interviews for the Rhodes Scholarship. This reception took place in an opulent all-male boarding school which in those years tolerated sexual abuse, although we finalists did not know it. I sipped my soft drink – the female candidates were judged too fragile or virtuous for anything stronger - and reminded myself that never before had women participated in such an occasion or opportunity. It had only been a few months, in fact, since women were finally allowed to apply for the scholarship, which was established in the early part of the century. I found myself wondering about the paths that had brought us women to this place. Who were we? And what would become of us afterwards?

Those questions stayed with me. After I completed my studies at Oxford some years later and entered the workplace, I would often run into other Rhodes Alumnae. I was always keen to compare verbal notes with the women about how our lives were getting along. A common theme in our conversations was our gratitude for the opportunities the scholarship provided – and, more broadly, for our good fortune to come along at the right age, in the right circumstances, when this and other opportunities had finally opened to women. We would talk about the excitement and also the responsibility of being the first generation of women that might have a shot at “equal opportunity.” We might even “have it all.”

But as life progressed, and became more complicated, we found ourselves asking, What exactly is the “all” that we are trying to have? I used to think that I was living the life for which earlier feminists had fought. I got married - when I was ready, to a person of my own choosing, who also supported equality. We had kids – mostly, again, at my own pace. And I also – again by my choice - pursued a career as fast-paced and demanding as my husband. I was in law, first in the corporate and financial sectors, then with a medical research foundation, followed by a stint in a BigLaw firm in Washington, DC, and finally as Senior Partner of my own international firm. I was successful at work as well as at home as a mother and wife. Perhaps this was the “it” that we female scholars hoped to have.

But then, some years ago, I met up with Deirdre Saunder, a close friend and Rhodes Scholar from Zimbabwe. She also led a full and rewarding life – and still does, as do I. She heard out my song of praise to our great luck as women who might finally “have it all.” But then she gently, but rightly, pointed out a paradox. We women can have it all, at least in the sense of careers as tough and rewarding as any man's (albeit at what often seemed to be a lower salary). We can succeed in ways never before possible for most women. But we still retained primary responsibility for managing the household, raising the children, and caring for aging kith and kin. We were driven to succeed, and largely did so. But we remained the default, go-to caretakers, and we accepted this role without question. Why? Is this really what women of our generation have achieved: a readiness to take on more than our fair share under the attractive euphemism of “having it all”?

Deirdre’s point dug into me. I thought “having it all” meant that women could achieve the same successes as men, and in the same jobs and positions. “Having it all” was supposed to mean equality of opportunity and equality of responsibility. We had finally had the proverbial “room of our own.” Yet we, and not our husbands, were cleaning the rest of the house!

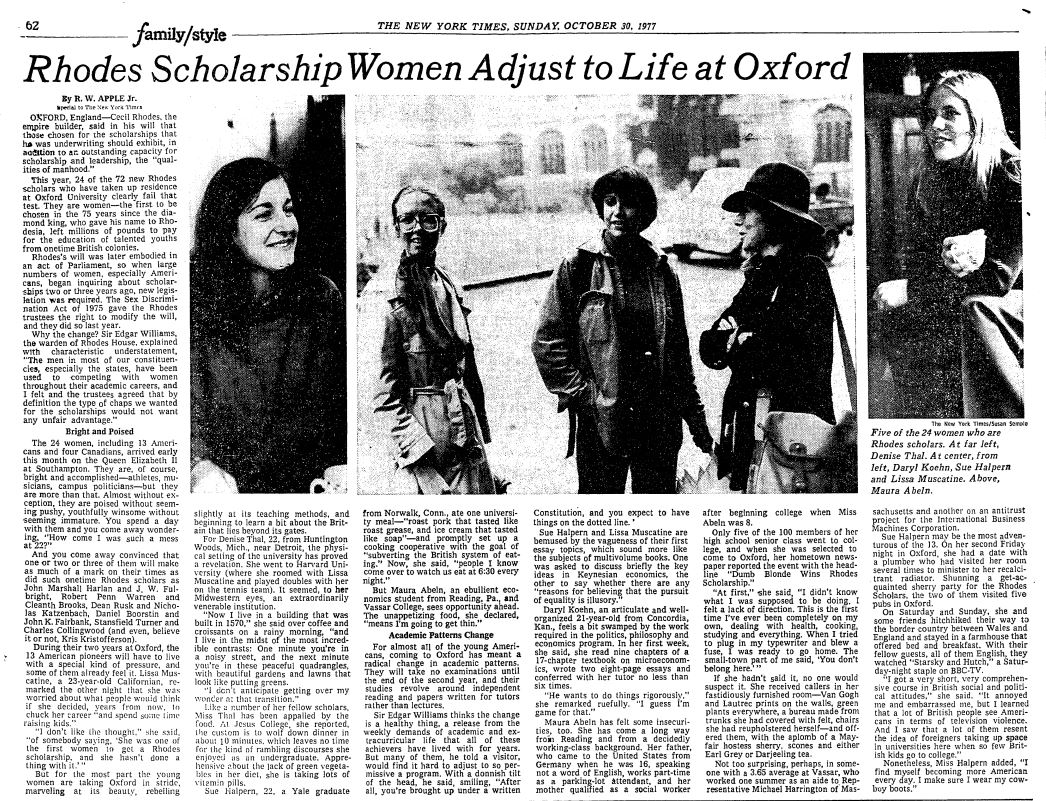

I began to think about the women Rhodes Scholars I knew, who by conventional measure should have as good a chance as anyone to achieve “success.” We were clearly able to take advantage of opportunities closed to earlier generations of women, which is real progress. But are we really free to take advantage of them to the same extent as men? And if so, do we? The accepted lore among and about Rhodes Scholars has been that female Scholars do not shine as brightly in their professional paths as their male peers. In my own home, I once heard a national secretary of a Rhodes Scholarship country say, as I was serving dinner to a score of guests and other scholars, “Well the women really have done nothing, they’re invisible and I don’t think any of them has been very successful.” Was this true? Certainly, I know of Rhodes women who have achieved high positions in traditionally male settings, such as in business, law, government, and science. But are these women exceptions to the rule? And is the “rule” misleading because it fails to take into account the disparity in absolute numbers – more than 4500 men had passed through the scholarship program before two-dozen women were elected in 1977 - and the fact that even the oldest female scholars were only just reaching the pinnacles of their careers?

I began to think that these questions were worthy of systematic investigation. If Rhodes women are in fact achieving as much as men, it would be sensible to lay out the evidence. They jury had reached a verdict. But I wanted to see the evidence. If we are not, in fact, as successful as men, then I wanted to know why. Perhaps the conventional definition of “achievement” was not appropriate. It seemed that a comprehensive survey of the first generation of women Rhodes Scholars might yield surprising results. What were their life choices and occupations, their values and beliefs, the families in which they were raised and the families they made? When I aired the idea of solving these puzzles, I was struck by the positive reaction from family and friends, who seemed to view this cohort of women, rightly or wrongly, as a marker of the progress of women and the women’s movement over the last 30 years.

I also wanted to follow-up on my long-ago questions about the paths that led some women to the Rhodes, and what would become of us. How are we leading our lives? When I canvassed various networks of women Rhodes Scholars, I was met by real enthusiasm. This provided me with the final encouragement to believe that the questions that were occupying me and my circle might also interest a larger group. And so, in the summer of 2004, I embarked on The Rhodes Project. It has generated some extraordinary results so far – which will be revealed soon in a forthcoming book. I expect that the program of research we are conducting will continue to do so. My hope is that our findings will be useful not only to academics but to everyone interested in women’s progress and the complex but absorbing problems of achieving real equality. In that sense, I hope The Rhodes Project will attract new people and new ideas to an important and continuing conversation.