Memory and perspective: two accounts of the life of Lucy Banda Sichone

Introduction by Kelsey Murrell

Lucy Banda Sichone was the first female Rhodes Scholar from Zambia. She was a civil and human rights activist, lawyer, journalist and founder of Zambia Civic Education Association (ZCEA).

At the Rhodes Project, we are passionate about the representation of women. We believe it’s crucial that women are visible in public life—in leading roles in films, in board rooms, as CEOs, in STEM and other fields—and within their own communities. We also know that women are too often narrowly portrayed or even misrepresented. This is why we strive to elevate women’s voices so that they may represent themselves, in their own words, as they do in our Profile Series.

Sadly, Lucy Banda Sichone, the first female Zambian Rhodes Scholar, passed away in 1998, six years before the Rhodes Project was founded. We will never be able to represent Lucy in her own words. Thankfully, much has been documented about Lucy in newspaper articles and manuscripts about her life. We have also had the great fortune to connect with Lucy’s daughter, Martha Sichone-Cameron, who has provided invaluable insight into Lucy’s life and legacy. This has led to the production of a profile of Lucy for our Profile Series and to Lucy’s selection as the subject of the first portrait of a woman Rhodes Scholar to hang in Rhodes House.

At times, Martha’s knowledge and memory of her mother differed from how Lucy was portrayed in various publications. As an organisation committed to meaningful and empowering representations of women, we found this to be intriguing and significant. We have therefore decided to publish, side-by-side, a piece written in 2007 by former Rhodes Project staff member Colette Gunn-Graffy, which is based on secondary materials, and alongside it, Martha’s corresponding reflections on her mother’s life which directly respond to the essay.

In the introduction to Writing Culture, a book that became a critical text in the field of anthropology, James Clifford argued that representations of others can only ever be “partial truths.” He gives the example of a photographer trying to represent a house. The resulting photograph is not actually the house; it is merely a representation of it. Furthermore, the photograph is limited in what it can tell the viewer. The photograph only reveals the house in a certain light and from a specific angle. A different photographer, taking the shot at a different time of day or from a different height, will produce a different representation. Neither photograph is necessarily “wrong”, each simply comes from a specific perspective. They tell part of the story. They are “partial truths.” We certainly do not claim that any one representation of Lucy Banda Sichone is the truth; on the other hand, neither do we contend that there are no such things as facts, or that striving to get to the bottom of them is a meaningless exercise (nor do we believe Clifford was making this argument). However, we do believe that hearing about Lucy’s life and legacy from a variety of perspectives, particularly from someone who knew her first-hand and so intimately as did her own daughter, will give us the privilege of having a fuller and richer understanding of this inspiring woman.

Below, the text on the left is the essay “Lucy Banda Sichone (1954-1998): Voice of Conscience, Daughter of the Nation” written by Gunn-Graffy. On the right you will find Martha Sichone-Cameron’s comments in response to Gunn-Graffy's essay.

Lucy Banda Sichone (1954-1998): Voice of Conscience, Daughter of the Nation

by Colette Gunn-Graffy

On August 28, 1997 the Zambian President Frederick Chiluba returned from a two-week trip to Europe and East Asia. As he advanced down the runway, shaking hands with the government and party officials who had come to greet him, a woman stepped out of the ranks and thrust a handmade banner in his face. It read, “Welcome to Zambia’s own Sharpeville, August 23, 1997.”

The banner was making a provocative analogy between the assassination attempt on former Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda five days earlier and the March 1960 Sharpeville Massacre in South Africa, when police had killed 69 people in an unarmed crowd that had gathered outside a police station to protest the apartheid practice of carrying passbooks. August 23, 1997 saw another incident of police firing on protesters; this shooting occurred in Zambia and was directed at Kaunda, who was also the leader of the opposition United National Independence Party (UNIP). Kaunda’s crime was that of holding a rally without a permit, a rally intended to launch a campaign of civil disobedience across the country. The permit, though applied for through the police, had not been granted. Kaunda was injured, his political ally Rodger Chongwe gravely so, but neither was killed by the shots.

On that day in August 1997, the woman at the airport standing up to President Chiluba was Lucy Banda Sichone, a 1978 Rhodes Scholar. A lawyer and public defender, Sichone was also a freelance columnist for The Post newspaper and the founder and head of the Zambia Civic Education Association (ZCEA). Although she was known for her aggressive criticism of Zambia’s political leaders, to hold a one-woman demonstration against Chiluba was risky. In Zambia, political opposition frequently faces violence or intimidation, and human rights abuses by police are common. Yet while her demonstration might have been foolhardy, it was also, according to Kenneth Kaunda’s son Major Wezi Kaunda, “the typicality of [Sichone’s] bravery. Not even men whom I know could do that.”

Fortunately for Sichone, when the police who were protecting Chiluba grabbed her and tried to drag her towards their vehicle, she resisted and was able to escape. In a column she wrote a couple of days after the incident, Sichone maintained that her escape was due in part to the presence of a crowd of street vendors who told the police that their “mummy [was] not [to] be harassed in any way.” In the same column, she also said that it was the man who grabbed her who needed protection and medical attention. “Under attack,” she crowed, “I do react like the Incredible Hulk."

This juxtaposition of images — protective nurturer versus enraged giant — emerges over and over again in Sichone’s own writing and actions, as well as in what others have said and written about her. In the last seven years of her life, she became something of a celebrity in Zambia. Letters written after her death called her “a voice of conscience” and “a great daughter of the nation;” yet over her lifetime she also managed to stir up a great deal of controversy, both personal and political. A mother of four biological and three adopted children, she devoted her life to protecting the uneducated and underprivileged from the abuses of government and law-enforcement authorities. In doing so, however, she was frequently brash and hard-headed. More than once, she threatened (or even engaged in) physical violence against those who insulted her or her family.

Indeed, there were many sides to Sichone. A biography (still in draft form) written by Austin Mbozi, one of her former colleagues, has tentatively been titled “The Many Faces of Lucy Sichone.” Yet, despite this – or perhaps because of this – attitudes toward her tended to fall into one or the other extreme. As Laura Mitti, another colleague of Sichone’s and now a columnist for The Sunday Times of Zambia, summed it up, “Either you like her or you hate her.”

“A Good Critical Mind”

Born Lucy Banda on May 15, 1954, Sichone grew up in Kitwe, the third largest city of what was then Northern Rhodesia and a hub for commercial activity in the Copperbelt region. As part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (which also included present-day Zimbabwe and Malawi) the country was administered by the British Colonial Office. Over the next decade, African nationalist parties campaigned to secede from the Federation – a goal that was finally realized on December 31, 1963 when the Federation was dissolved completely. On October 24, 1964, Northern Rhodesia officially became the Republic of Zambia, led by President Kenneth Kaunda.

The fact that Sichone came of age in the first decade of Kaunda’s 27-year presidency would greatly influence her views of governmental intervention in the economy. Under Kaunda, control of the economy was centralized and many socialist economic policies were put into place, including government subsidies to farmers and consumers. In the 1960s, Zambia’s chief export was copper – as it still is today. At that time, however, the Zambian copper mines were state- owned, and as such, were able to offer free education, health and social services to their workers and their families. Sichone’s own father, Robert Banda, was a miner in the Nkana mine of the Zambia Consolidated Copper Mines (ZCCM) company. Later in life, she wrote in one of her columns that were it not for UNIP socialist policies such as those described above, she would still “be living in Buchi [Kitwe] selling tomatoes by the side of the road.”

Yet even if Sichone did not grow up to sell tomatoes, she maintained a deep connection with the people and customs of Kitwe. In his unpublished biography, Mbozi describes her as feeling “more at home” in the rural countryside, “beaming with excitement, eating with simple-looking villagers, and [much less] emotional [than she was] when in the city.” She enjoyed the sense of community the villages offered — particularly in the east where she was from. Families settled together in compounds, rather than living on their own. “She loved it all [the village community] and encouraged us to buy local food to provide the much needed market for the people.”

Given this strong identification with rural Zambia, it is perhaps surprising that Sichone chose to apply for the Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford. Even more extraordinary is the fact that in doing so, she was reacting against both her mother — Lily Mulenga, a “traditionalist” who “believed that girls should not go to school but should prepare for marriage” — and the cultural norms she had grown up with, since the majority of Zambians do not complete ninth grade.

It is difficult to say exactly what it was that drove Sichone to pursue education to the degree she did, but, according to one of her recommenders to the Rhodes Scholarship, she came across as someone “who will naturally aim for the very best possible.” Before applying to the Rhodes, Sichone had attended an all-girls secondary school and had received a BA in Law from the University of Zambia (UNZA). Noted for her “well above average” intelligence, she stood out in school for her critical mind and her “courage to stand up for her conviction[s].” The fact, for instance, that in the second, third, and fourth years of her LL.B. program at UNZA Sichone was the only female, certainly did not hinder her in contributing to discussion.

Even at a young age, Sichone seemed to have a great sense of duty. Decades before she came to condemn government hypocrisy in her newspaper columns with allusions to the New Testament, she was active in several Christian youth groups, and through them, leading efforts to get young people off the streets. As she told one of her recommenders, she wanted “to do something worthwhile in life.” To Sichone, education had an essential role to play in fulfilling that duty. In 1996, two years before her death, The Post ran a profile article on her entitled, “My greatest mistake,” in which she says, “I think my biggest mistake was to go to school because this made me become aware of my abilities and rights, resulting in [a] failure to keep quiet about my informed stand on issues.”

Certainly by the time Sichone applied for the Rhodes Scholarship, she had recognized and embraced this “failure.” “After [I receive my Masters from Oxford],” she wrote in her application essay, “I intend to pursue a career in teaching [as a lecturer], it being my belief that students learn a lot more from lecturers than what is written in their text books. I hope I will be much more than just a lecturer to my students.”

A Seemingly Enigmatic Woman

As it happened, it was a second bachelor’s degree that Sichone pursued – in Philosophy, Politics and Economics (PPE) – and it did not prove easy, at least initially. Having won the Rhodes Scholarship in 1978, she applied to Somerville College at Oxford. Although the college was eager to accept her, Sichone’s desire to read for a BA in PPE caused some consternation among her potential tutors, as she had little background in the subject. Their solution was to admit her as if she were an undergraduate, so that she would have a third year in which to take her degree. (Typically, those taking a second BA in a subject related to their first BA completed the degree in two years.) Certainly Oxford, with its gleaming spires and old-boy traditions, was worlds away from the poverty and rural customs with which Sichone had grown up. Judging by the first-year reports of her tutors, it took some time for her to adjust to the course. Although she showed enthusiasm for the work, Sichone’s level of writing was considerably lower than that of her peers, and she clearly was not used to the depth of analysis her tutors expected. Early on, several tutors expressed concerns that, even with the third year, she would not be able to cope with the demands of the subject.

It is possible matters were further complicated by the fact that, in departing Zambia for Oxford, Sichone had also left behind a four-year-old daughter, Martha, and her fiancé, a Zambian police cadet called Martin Sichone. Whatever her feelings about this parting, it is doubtful Sichone shared them with her new acquaintances at Oxford. Both the Principal of Somerville, Barbara Craig, and Sichone’s moral tutor Judith Heyer, commented on her formality — her seeming need “to keep at a respectful distance.”

Even amongst her peers, Sichone “generally … didn’t open up. … [She] kept to herself more.” According to Susan Karamanian and Isha Ray, two of her friends at Oxford, Sichone was an enigma to those who knew her only by acquaintance. In appearance, she stood out for her insistence upon wearing layers and layers of clothing, "[r]egardless of the season." But her behavior, at least "in large groups...was reserved, you could even say shy."

However, those who lived with Sichone in Somerville’s Holtby Hall saw a different side to her. There she was known for being a powerful, often unapologetic voice. “She had strong opinions on nearly every issue. She could disagree with you bluntly, saying, ‘You are wrong.’ Or ‘Ah-lah, you don’t know anything.’ She simply did not believe in little niceties or social airs.” And yet, in dispensing her advice as fact, Sichone also came across as “the hall’s matriarch,” and it was often she who took care of the women in her group and listened to their problems.

By her second year at Oxford, Sichone’s work had greatly improved. Her tutors’ pleased remarks indicate the remarkable strides she had made; indeed, she was writing and arguing on a par with her peers. Sichone’s views, however, remained her own, which “made her a refreshing student to teach.”

It was during this year that Sichone married her fiancé, and in petitioning the Governing Body to allow her to continue her studies also revealed that she was due to have a baby the following autumn. Although she did take Martin’s name, she asked that those in College continue to call her by her maiden name Banda.

At the end of October 1981, Sichone returned to Oxford for her third and final year, having left her new baby, Robert, under her mother’s care in Zambia. Her work throughout that year continued to win praise from her tutors, who predicted further good results in her exams. Tragically, on June 9, 1981, just as she finished her last exams, Sichone received word that her husband Martin had been killed in a car crash. She was also informed that a plane ticket had been purchased for her (by the Nchanga Consolidated Copper Mines, who were to employ her on her return to Zambia) to fly home that very night. Several of Sichone’s friends took her to buy mourning clothes. Then, according to Karamanian, “we helped her pack up her things and she left that evening. I never heard from her again.”

The following autumn, Daphne (now Baroness) Park, then Principal of Somerville College, received a letter from Sichone, thanking her for all that had been done for her in the immediate aftermath of Martin’s death. “It is not something I am likely to forget.” Although Sichone had clearly been through a time of mental anguish, she assured the Principal that she was “okay now.” Her son, she wrote, “is the exact replica of my husband — it is quite painful to look at him sometimes. But he does bring me some happiness and it’s mainly due to him that I revived so quickly.” Sichone also praised the Nchanga Consolidated Copper Mines (NCCM), her current employer, as “invaluable” to her recovery. Not only had the NCCM arranged for her flight and the transportation of her belongings back to Zambia, the NCCM had also addressed a problem nearly as disastrous as her husband’s death: according to Zambian custom, Sichone’s in- laws had stripped her and her children of everything they (and her husband) had owned. Shortly thereafter, NCCM had supplied her with the living essentials — from “teaspoons … to cooker and fridge” — she needed to rebuild her life.

This experience — although temporary — of being robbed of all that she possessed deeply affected Sichone. “[The] way I was left destitute has given me the idea of what I want to do … start a Legal Clinic for widows and orphans — who are not as well-equipped to face life after a husbands’/fathers’ [sic] death.”30

This idea was clearly the seed out of which the grassroots work of the Zambia Civic Education Association (ZCEA) grew. Before Sichone would pursue this dream, however, she took a stab at more traditional top-down political reform. In 1991, she resigned from her position with the mines to pursue a position within the UNIP party.

“The Only Young Person who [Acknowledged] what UNIP had Done for Us”

In 1964, the year Zambia gained independence, it was one of the wealthiest countries in Africa. Nearly half a century and three democratically elected (in theory, at least) presidents later, it is one of the poorest and most indebted nations in the world. According to the World Bank’s 2004 estimates, 73 percent of the Zambian population now lives below the poverty line, and the average life expectancy is just 36 years.

Finger-pointing typically begins with former President Kaunda’s nationalization of the copper mines; yet in the decade following independence, his socialist policies were relatively successful. The price of copper, Zambia’s primary export, increased, as did the real GDP — by approximately 2.3 percent per annum.32 But, in 1975, following a massive increase in the price of oil, the price of copper plummeted. Effect was that between 1975 and 1990, the country’s real GDP per capita declined 30 percent.

As Zambia’s economy worsened, it borrowed heavily from foreign lenders, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In the 1980s, the IMF began to put pressure on Kaunda to restructure the economy using a number of measures including the elimination of subsidies to farmers and devaluing the currency. This led to huge increases in the price of food. Riots broke out in the country’s urban centers, and Kaunda moved away from the IMF’s structural adjustment plan to institute an ultimately unsuccessful economic recovery program of his own. In 1989, a further agreement was reached with the IMF, which, among other requirements, required Zambia to begin privatizing its government-owned industries. As living standards in Zambia declined, so too did popular support for Kenneth Kaunda.In 1972, Kaunda had banned all opposition political parties and instituted a one-party system of government — a move that kept UNIP in power for nearly three decades. Yet in 1991, faced with growing public dissatisfaction, he was forced to call a multi-party election. During this time, one of Kaunda’s most popular opponents was Frederick Chiluba, leader of the Movement for Multi- Party Democracy. Promising political and economic reforms, MMD swept both the presidential and parliamentary elections, installing Chiluba in the seat that had belonged to Kaunda for nearly 30 years.

At this time, most Zambian intellectuals and elites, if they had not already done so, defected to the MMD. Lucy Banda Sichone was one of the few to hold out. Her allegiance was partly out of gratitude; after all, it was thanks to the socioeconomic policies of UNIP, not the IMF’s structural adjustment programs, that she had been fed, clothed and educated as a child. “The heritage of UNIP to my generation,” she wrote in a later article, “had to be preserved for my children and their children.” Yet, it was not out of loyalty alone that she dug in her heels.

According to Mbozi, Sichone wanted to ensure there would continue to be a viable opposition to the new regime. Without such an informal system of checks and balances, the country would be a two-party state in name only. Thus, rather than shackle herself to the MMD — even if doing so would, no doubt, have landed her a cushy position within the new government — Sichone left herself free to act as a very vocal “check.”

Sichone stood out at a time when most of her intellectual peers were fleeing Kaunda’s circle. She was quickly appointed to the Central Committee as Chairperson for the Women’s Affairs Sub-Committee, as well as to the UNIP’s Constitutional Review Commission. In these positions, Sichone spent about a year under Kaunda’s tutelage, observing his interactions with common citizens and his consultations with other political leaders. During this time, she developed a great respect for the former president, whom she praised for his skills “as a statesman, [and his] wisdom.”35 In later years, she frequently came to the defense of his person and reputation, both as a columnist and as a political activist – for instance, following the attempted assassination in August 1997, she held a press conference, as well as the aforementioned “Sharpeville” welcome of Chiluba at the airport.

Yet, only a year after joining the party, Sichone resigned — just “a step,” she believed,“ahead of expulsion.” Although she may have admired the UNIP’s socioeconomic policies, she was also intent on party reform. The trouble was that many of the UNIP’s senior members — including Kaunda — were not.

In 1991, after Kaunda lost the presidency, change inside UNIP had seemed possible, even inevitable. Kaunda had announced his intent to retire and threw his support to Kebby Musokotwane, a young and intelligent former Prime Minister, to succeed him as party leader. Those who opposed this move, mostly conservative members of the party, Sichone lambasted publicly as sycophants “using [Kaunda’s] coat tails for [their] continued survival in politics.” In fact, she told Kaunda, “[You] should take all of them with [you when you retire.]” Although Kaunda chastised Sichone for the “rudeness of [her] language” he also acknowledged the “truth” of her views, and according to Sichone, “it was at that meeting that KK [sic] took me under his protection.”

But this protection only extended so far. Following intra-party elections, Sichone joined the “new look” (Musokotwane-led) UNIP as the Secretary for Legal, Constitutional, and Parliamentary Affairs. Believing that as the leadership of the party evolved, so should its image, she used the power of her position to advocate for several reforms. Among the most controversial of these were the replacement of Kaunda’s image on the UNIP membership card with that of a hoe, and a new dress code of jacket and tie, rather than the “safari suits” made famous by the former president. For this, she was labeled a traitor by many of the “old guard” members of the party, and — according to Sichone — she lost the support of Kaunda himself.

In addition, Sichone’s behavior following the discovery of the “Zero Option Plan” set many party members against her. In February 1993, The Times of Zambia published excerpts of a document known as the “Zero Option Plan” which called on UNIP supporters to render the country “ungovernable” through acts of civil disobedience and armed insurrection. Sichone condemned the authors of the document, arguing that whatever the crimes of MMD, it was still a democratically elected government, and to destabilize it was to commit treason. Then, a week or so later, when President Chiluba declared a state of emergency on account of the document, she lashed out at him as well. To many in both parties, this volte-face seemed completely illogical and not a little misanthropic: if both parties were in the wrong, who, then, other than Lucy Banda Sichone, was in the right? Yet, what most partisans did not seem to realize was that Sichone was not standing up for a particular group, but for an ideal – that humans possess certain rights, among them to seek recourse via negotiation and due process, rather than through violence, whether that violence is perpetuated by the government or by opposition parties.

However, Sichone baffled and angered people in the way in which she seemed to make her own rules. While a member of the “new-look” UNIP, she began an affair with Kebby Musokotwane, who was not only party leader but a man married with children. According to Mbozi, the couple were relatively open and honest about the relationship — at least once it had been exposed by the media — which likely saved them from greater embarrassment and even won them some public sympathy.38 Their plan to marry, however — casting Sichone in the role of second wife — and the revelation that she was pregnant with his child, caused much outrage and controversy. By the time the story of “Kebby and Lucy” had been exposed by the press, it was 1995. Sichone had left UNIP several years earlier, but Musokotwane at that time was party president on his way to running for president of the country in 1996. Questions not only of morality but also of logistics preoccupied many Zambians — how would Musokotwane keep two wives in the statehouse? And which of them would be called “first lady?”39 Sichone’s simple defense was that there was nothing wrong with polygamy if all three parties accepted it; however, there was never any indication that Musokotwane’s first wife, Regina, had done so. In fact, in an interview with The Post, what she had actually said was, “Naturally I’m not happy [about Kebby and Lucy]. No woman would [be].”

Sichone responded with characateristic defiance to the criticisms of her private life. Comparing herself to other public “greats,” such as Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, and Nelson Mandela, she wrote, “The reason why we make ourselves available to the puny stone throwers is because we know that the pebbles will not dent our nobility of character nor will it hinder the good that is done through our work.” But in 1996, before the couple could be married, Musokotwane died of a sudden illness. “Widowed” a second time, Sichone did not put her grief on display — though she did pointedly warn the media “to leave the dead to rest in peace or risk reprisals from yours truly.”

An Authority on Everything

If Sichone’s views were too revolutionary for party politics, they found a home in The Post newspaper. In Zambia, there are three national daily newspapers: The Post, The Times of Zambia, and The Zambia Daily Mail. Of these three, The Post is the only one that is not state- owned. It also has the highest readership — in a country in which 37 percent of the population reads a newspaper, The Post claims 39 percent of this readership. While journalists for the state-owned newspapers face a great deal of censorship, Post journalists have been harassed and intimidated — even imprisoned — for their criticisms of Parliament and government officials.

Sichone fit right in, of course. In 1993, she began writing her own weekly column in The Post called “Lucy on Monday.” Abundant with vitriol, but never with apology, the column provided her with a platform to attack the government for what she perceived to be acts of hypocrisy and pettiness. With language as passionate as it was often pompous, she would explain just exactly how officials had embarrassed and humiliated her nation.

The Vice President General Godfrey Miyanda, Sichone condemned as a “hypocrite … [who] suffers … verbal diarrhea.” In another column, she described Zambian Members of Parliament as “eunuchs lack[ing] the most basic human qualities of integrity, courage, vision, concern for other people, patriotism and commitment,” who did not understand that “a job does not make a man. It is a man who makes the job.”

The MMD, a frequent target, she called:

A drunken man … [who] has soiled its trousers with fraudulent elections, unlawful usurpation of power the stench of which has naturally attracted large flies and the attention of innocent children and citizens … My advise [sic] to the MMD is that the only way to get rid of green flies, excited children and the denunciation by law abiding men and women everywhere is for the party to get behind the nearest big tree, grab a handful of leaves and clean up as best as possible.

Yet Sichone did not reserve her invective solely for the MMD. After parting company with UNIP, she kept her critical eye trained on its members, and continued to question their actions in her columns. And despite her personal affection for Kaunda, the former president remained a target of many of these written diatribes. Most notably, Sichone took issue with the fact that, despite his apparent retirement in 1992, two years later he was back on the political front line, styling himself as the people’s choice against the incompetent MMD government. Perhaps more treacherous in her eyes was the fact that, in 1995, Kaunda stood against the incumbent Musokotwane for leadership of the UNIP party and won by a landslide – whether the “Kebby and Lucy” scandal had anything to do with this is unknown. In 1996, in anticipation of the national presidential election, Kaunda announced that he would travel the country to collect signatures from his supporters to show that people wanted him back in politics. Completely opposed to Kaunda making any bid for presidency, Sichone vowed to conduct a similar tour; instead of pro-Kaunda signatures, however, she swore she could collect at least 3 million anti-Kaunda signatures — evidence that would contradict his claim of nationwide support. (Neither of them ever did collect the promised signatures.)

To Sichone, Kaunda’s return amounted to “betrayal” of the party, and she went on to criticize his “failure,” in that he “had never groomed a leadership who could continue after him.” Indeed, she wrote, “it must be obvious that there is nothing KK can do now that will add to his stature as a statesman,” as opposed to Nelson Mandela (a personal hero of hers), whose “immortality will be assured by the critical role he will continue to play as an ordinary member of the ANC in the humane task that South Africa faces today – that of reconciliation and nation- building.”

How Can One Woman Defeat Us?

Like Kaunda, however, Sichone could not seem to back down from political pursuits — except in her case, these pursuits evolved into grassroots reform. According to Mbozi, Sichone believed there were “two things indispensable in any democracy: a strong opposition and a well-informed citizenry.” Towards this end, in September 1993, Sichone founded the Zambia Civic Education Association (ZCEA). Dedicated to providing civic education and legal aid to those Zambians who would not otherwise be able to afford it — in fact the vast majority of the population — ZCEA started by conducting workshops and public meetings in rural areas. Run by Sichone, these workshops were friendly rather than formal, and her open, frank nature won the respect and attention of villagers and their chiefs.

One of the best-known issues that Sichone dealt with in her workshops was the 1995 Land Act. As part of President Chiluba’s attempt to liberalize the Zambian economy, the Land Act was intended to promote foreign investment in the country and its industries. Prior to this piece of legislation, land had no monetary value and could not be privately owned, though a small portion could be leased. Approximately 90 percent of the land was administered by tribal chiefs, with the remaining ten percent divided between the state, councils or private title deed owners.

Yet such a system was antithetical to Chiluba’s new approach. Having inherited a debt of approximately U.S. $7 billion, the MMD government turned to the World Bank and IMF for financial support; in return, Chiluba had to implement certain economic reforms conducive to privatization and diversification of industry and investment.50 The World Bank maintained that in order to encourage development, customary tenure — the communal holding of land — should be replaced with a more secure form of ownership in the form of land titling and registration. Thus, under the legislation, all previously tribal-held lands were repossessed and vested in the president of Zambia to hold in trust for the Zambian people. The Act also put a monetary value on the land and gave the president the power to distribute land to any person, whether Zambian or not. In effect, the law transformed many villagers into squatters overnight after their once communal land became the private property of government- sanctioned investors; further, as Sichone wrote furiously in one of her articles, “the money paid by the so-called investors does not go to compensate, resettle or rehabilitate the villagers.…[The Land Act] means the liquidation of an entire way of life, a death sentence for both the people and their livestock.”

In the ZCEA-sponsored workshops she held in rural villages, Sichone would explain the Land Act (among other legal issues) to her audience, as well as their rights under this law, and then would take questions. Several times she did this in the presence of MMD officials who tried to discredit her. She also represented several displaced villagers, who had been accused of being squatters,in court. Unfortunately, Sichone could not get around the fact that what the investors had done was in fact legal; thus, she could not win these cases in court. Undeterred, she directed villagers to ignore the law and resettle on the farms which had previously been theirs. She also encouraged them to use armed force if threatened. As a result, Sichone’s fame spread quickly; both among the village headmen who invited her to conduct workshops, as well as among government officials who attempted to threaten those chiefs who invited her. So successful and widespread was Sichone’s campaign on this issue that National Secretary of the MMD Michael Sata is reported to have lamented, “We as politicians, how can one woman defeat us?”

Another abuse of power which Sichone attempted to expose and subvert through civil education was the passing of the 1996 national constitution. Following MMD’s victory in the 1991 elections, the government set out to adopt a new constitution for the country. A Constitutional Review Commission was created, and Sichone was among those appointed by President Chiluba to travel around the country collecting oral and written statements from the people of Zambia as to what they wanted to have in their constitution; this information was then supposed to be applied to the drafting of the new constitution. In reality, however, the government rejected many of the Commission’s recommendations, including: that the President should be elected by at least 50 percent of the electorate (instead, it was legislated that a plurality was all that was necessary), that Cabinet Ministers be appointed from outside parliamentary ranks to ensure separation of powers, that a Constitutional Court should be established, and that the chairperson of the Electoral Commission should be ratified by Parliament. Additionally, government ministers included a clause that bars Zambians with one or more foreign parents from standing for the presidency.

In response, the ZCEA and several other NGOs organized a conference in Mulungushi from March 1-10, 1996 at which the “Citizen’s Green Paper,” an alternative to the one endorsed by the government’s “White Paper,” was drafted. The international community, too, voiced concern; Britain’s High Commissioner Patrick Nixon withheld a £10 million grant to Zambia because of the draft constitution. Yet despite this, and despite the fact that several MPs resigned or walked out of Parliament in protest during the constitutional debates, the constitution passed in Parliament and was signed into law by Chiluba on May 28, 1996.

Undeterred, Sichone merely added the truth about the constitution of 1996 — that the government had rejected the will of the people in its drafting — to her workshop agenda.

In addition to counseling Zambians on their legal rights, Sichone often represented them in court as pro bono clients. Stories and information gathered from village workshops had made it clear that Zambia’s criminal justice system was a great source of human and constitutional rights abuses.55 The average Zambian possessed neither the legal knowledge nor the financial resources to defend his or her rights; torture and trumped up charges (or no charges at all) commonly followed political arrests. Indeed, two of Sichone’s high-profile cases followed acts of political extremism: in one, a shadowy group known as the “Black Mamba” set off explosions and sent death threats to MMD officials in an effort to force the government to withdraw the 1996 constitution; the other was a short-lived coup led by “Captain Solo,” a drunken army officer who, along with his regiment, was simply fed up with the nation’s growing poverty and unemployment under MMD. Mass arrests and detentions of UNIP-connected officials followed both incidents, and Sichone was directly involved in the defense — and subsequent acquittal — of many of these individuals.

Occasionally, villagers would question Sichone’s motives because of her UNIP past. Their unease stemmed from suspicions that no one would pursue philanthropy in the absence of any personal or political gain. A far greater obstacle to Sichone’s workshops,however, was the Public Order Act, a law issued by the Chiluba-led government requiring that anyone who wished to hold a public meeting apply for a police permit seven days in advance. Zambian police could be very selective in granting permits; NGOs, opposition parties, and other civic interest groups were regularly denied them, whereas the MMD continued to hold demonstrations and rallies without permits. An added frustration for Sichone was that, in rural areas, the nearest police station was often quite far from the village where the ZCEA was to hold its workshop. It was a blow to travel, in some cases, as much as 60 kilometers, only to be arbitrarily denied a permit. Of course, even if she were denied the permit, she proceeded with the workshop, often battling with or attempting to deceive members of the police. Sichone was counting on the fact that if police did arrest her, a huge local and international outcry would follow, focusing international attention on the MMD government. According to Mbozi, Sichone’s philosophy of civil disobedience was taken from Martin Luther King Jr.: that in breaking unjust laws, and in accepting the penalty for doing so, she was upholding justice overall.

I Am Not Hiding

Though her personal views of justice may have been similar to Dr. King’s, Sichone was hardly arguing for nonviolence. She did not shy away from violent confrontation — in fact she encouraged it when she thought it would be effective. Even her columns frequently read as challenges rather than commentaries. In response to a demand by some Members of Parliament for her arrest for holding a public demonstration without a permit, Sichone writes:

I can only say that mob action wherever it occurs is the worst form of cowardice ever known to man. When the same mob mentality occurs in an august institution such as parliament, it means the tragic and painful death of the country which we Zambians are not going to allow. [MP] Earnest Mwansa should know that my office is just up the road from the National Assembly — I challenge him to come up and attempt to effect a citizen’s arrest for exercising my right to free speech as enshrined in the constitution and I am sure we will learn something from the experience.

For Sichone, even if this outspokenness was on the cusp of impropriety — or, in Zambia, illegality — it remained her natural right. In his biography of Sichone, Mbozi compares her articles to a blunt weapon that she would “hammer” against her opponents; if they reacted against her, she would “hammer even harder …[until] she hit the final blow and crush[ed] them into silence.” In fact, some of her more powerful opponents were trying to do exactly the same thing to her. One of them, Vice President Godfrey Miyanda, was frequently involved in the MMD’s attempts to gag privately-owned media. In trying to silence Sichone, he proposed government regulation of NGOs, and raised a point of order against her in Parliament. In a letter (later reprinted in The Post), Sichone responded to his accusation of malicious character assassination by saying:

I should categorically state that your job as Vice-President of Zambia gives me the right and mandate to judge your public actions and pass a verdict without us having a personal relationship whatsoever. My right to criticize and pass judgment on your actions as vice president arises from the fact that I am criticized and judged by the world as a Zambian citizen on the basis of the image that you, as vice president, project to the world at large.

In the end, however, the Zambian government sided with Miyanda against the right to free speech. In January 1996, Miyanda succeeded in raising a Parliamentary point of order against Sichone, The Post’s editor-in-chief Fred Mmembe, and managing editor, Bright Mwape. Earlier in the month, the Supreme Court had ruled that sections of the Public Order Act — the law that required people to obtain police permits for public gatherings — were unconstitutional. In Parliament, Miyanda had condemned the Court for this ruling — and the three journalists, in turn, had been critical of his remarks. That prompted a prosecution for contempt of Parliament, and, when none of the three appeared in court, they were tried in absentia and sentenced to imprisonment for an indeterminate period. Although Mwape was immediately detained, Sichone and Mmembe escaped jail by going into hiding; at the time, Sichone took her youngest biological child — then a six-month-old — with her. While in hiding, both she and Mmembe continued to write newspaper articles for The Post that challenged the view that Parliament was supreme in these circumstances. In one of these articles, entitled “I am not hiding,” Sichone wrote that “Respect … (even for Parliament) is earned, not worn like a skirt or trousers by virtue of a job or Parliamentary office.”

It speaks volumes about Sichone’s popularity — and respect — among the Zambian people that even though public notices offered 2 million kwachas (approximately $1700) for information about her whereabouts, not one person came forward to “sell” her to the police. Nearly two months later, High Court Judge Kabazo Chanda decreed that the conviction was unlawful and lifted the three columnists’ jail sentences.

We Cannot All See the World Through Your Eyes

Sichone saw herself as a champion of the people. Frequently in the forefront of conflict with police and government authorities, she put herself at risk to help ordinary Zambians. For her, the protection of human rights was an active process, not one that could be undertaken simply behind a desk or through the distribution of a study or pamphlet. Although it was “not done,” Sichone criticized some Zambian NGOs which she felt did not live up to their stated goal of protecting human rights, but were instead “empty drums who make useless noise [in order to secure] permanent and pensionable employment [for themselves.]” In particular, she chastised the Human Rights Commission (HRC) for directing Zambians whose rights had been abused in the workplace to file with the Industrial Relations Court (IRC), which required a K26,000 filing fee before proceeding — equal to the annual pay for a Zambian civil servant. Unless it was offering to pay these people’s legal fees, she thought the HRC was offering them no help whatsoever:

The abuse of rights [is due to] the fact that the victims have no redress in a country in which the judicial system is not only irrelevant to the common man but obscenely expensive, a country that has priced the industrial tribunal beyond its constituents, a government that sets up a Commission for human rights that is a fallacy to mock victims of abuse.

In response to these criticisms, Nagande Mwananjiti, the executive director of AFRONET, wrote “The trend among global human rights groups is to specialize … we cannot all run legal clinics or else other areas will be left wanting.”

It may be said that Sichone wrote and acted in the extreme — she steamrolled over the arguments of the opposition and physically put herself at risk by confronting authority head-on, armed with nothing more than a weekly newspaper column and her own sense of injustice and outrage. For all her work for the downtrodden, Sichone seemed to have had little tolerance, or patience, for those whose actions and beliefs did not resemble her own — and certainly not when it came to what should be done for the development of her country and people. Whether it meant attacking the students of the next generation as dim and passive for failing to demonstrate against Pastor Nevers Mumba, the former vice president of Zambia, or publicly disdaining her former colleagues who remained loyal to UNIP (after she resigned) as the “living dead,” she was particularly critical of those who came from backgrounds similar to hers and yet made different choices.

“We cannot all see the world through your eyes, Lucy,” General Benjamin Mibenge once wrote in a letter to The Post. “I wish you successful crusading.”

“One of the Most Courageous Human Rights Activists”

Sichone spent the last years of her life in declining health. But despite her illness and lack of energy, she would not break her commitment to the rural poor of Zambia. In the communities where she held her workshops, she had become something of a celebrity — to the point that her inability to attend a workshop, for illness or other reasons, caused widespread disappointment. According to Mbozi, for some people it seemed “just taking a glimpse at Sichone whom they had heard so much about would satisfy them …. For us organizers we were sure of getting attention, admiration and pride when we identified ourselves as associates of Sichone as a person rather than with ZCEA as an NGO.”

On August 23, 1998, Sichone died, reportedly from pneumonia. When the public heard of Sichone’s death, “it seemed as if a dark cloud had descended on the country.” Newspapers printed letters from people mourning her passing, and prominent Zambians, including Kenneth Kaunda, described her death as a “tragedy,” and a “terrible loss.” Against popular opinion, the government refused to grant Sichone a state funeral.

Certainly, Sichone left a bad taste in some people’s mouths. She was confrontational and professed outrageous and polarizing opinions, more so than is customary in public life. But this made her popular with others, and also widely known. Indeed, were it not for her untimely death, Sichone might have run for president as an independent in 2001. She told journalist Gideon Thole, “The best way I can improve the people’s welfare, is by being the head of state and I’m preparing myself to do just that.” (It is noteworthy that the late president of Zambia, Levy Mwanawasa, had a similar background to Sichone: born and brought up in the Copperbelt province, Mwanawasa attended University of Zambia from 1970-1973 where he received a BA in law, and practiced as a lawyer before being elected president on the MMD ticket; he was not, however, a Rhodes Scholar.)

It is also interesting to note that, in her industriousness, determination and magnified sense of self-importance, Sichone was not unlike Cecil Rhodes, who was himself a controversial figure. Like Rhodes, she had a gift for bringing people together and igniting their passions — whether for or against her — as well as tendency to bend, and often break, rules that did not suit her. Yet Sichone always rooted for the underdog — indeed, she was herself an underdog — and in that, their paths diverge.

Had Sichone submitted her application to the Rhodes Scholarship in these last few decades of applicant “grooming,” it is debatable whether she would have been selected. By today’s standards her CV was hardly illustrious, and her writing, certainly not up to snuff. It is true also that her Rhodes Scholarship and Oxford degree did not provide a “passport to success” in conventional terms — as one obituary mentioned, few of the people who touched her daily life knew she had studied at Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship. Instead, the “introductions” Sichone reaped were political and cultural, for if Oxford made her conscious of disparity, it also opened her eyes to possibilities for change. Although Sichone surely had her tongue in her cheek when she acknowledged her extensive education as her “greatest mistake,” it may be that the understanding she acquired also set her on a long and rocky path. She once wrote: “It is the hope of seeing justice done one of these days that makes the … depression [born of watching the top Zambian executives grow rich from privatization while the rest of the country continues to starve] bearable; at any rate, I do get some relief from writing even if nobody else is listening.”

But people clearly were listening, in Zambia and beyond. In her lifetime, Sichone’s work won her the “Courage in Journalism” Award from the International Women’s Media Foundation as well as the Media Resource Council’s Patriotic Citizen Prize. She also received the International Bar Association’s Bernard Simons Award — regarded as the most prestigious award in the field of international law.

And, in a non-industrialized, non-western country, it may be argued that her voice rang out more loudly and clearly than it would have had she settled, like many of her fellow Rhodes counterparts, in the UK or North America — as did so many of her fellow Rhodes counterparts.

Works Cited:

- Alex Vines, “Zambia: Elections and Human Rights in the Third Republic.” December 1996. Human Rights Watch. 31 May 2007 <http://hrw.org/reports/1996/Zambia.htm>.

- Angela Wood. “Back to Square One: IMF wage freeze leaves Zambian teachers out in the cold. Again.” Global Campaign for Education. 3 June 2005. 11 June 2007<http://www.campaignforeducation.org/resources/ Jun2005/back_to_square_one_tcm8-4743.pdf>.

- Austin Mbozi, The Many Faces of Lucy Sichone: A First Hand Account of Zambia’s Human-Rights Heroine of the mid-90s (unpublished)

- Gideon Thole. “Zambia: Lucy Banda Sichone — champion of human rights.” ANB-BIA Supplement, Issue 357 — 1 Dec 1998. 25 January 2007 <http://ospiti.peacelink.it/anb-bia/nr357/e09.html>.

- "Human Rights in Zambia.” International Bar News. April 1998. p. 21.

- Human Rights Watch. “Zambia.” World Report 2001. 22 June 2007 <www.hrw.org/wr2k1/africa/zambia.html>.

- Lucy Banda, “Curriculum Vitae.” 13 July 1977.

- Lucy Banda Sichone to Daphne Park, 17 October 1981. Private letter

- Lucy Sichone, “Zambia: Land law is a setback to the dark ages.” Global News. 1 October 1998. 18 June 2007

- <http://www.ms.dk/sw24932.asp>.

- “Lucy was an Inspiration.” September 2008. Legal Resources Foundation. 4 April 2008 <www.lrf.org.zm/Newsletter/September/lucy.html>.

- Peter Burnell, “Case Study Two: Politics in Zambia.” Politics in the Developing World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

- Somerville College Report Forms, Michaelmas Term 1978 – Hilary Term 1979.

- Somerville College Report Forms, Trinity Term 1980.

- Somerville College Report Forms, Hilary Term 1981

- Susan Karamanian, “Lucy Banda Sichone (1978),” Somerville College Report, 1999.

- Susan Karamanian. Personal Interview. 5 February 2007.

- Virtual Zambia.” 2005, Biz/ed. 1 May 2008 <http://www.bized.co.uk/index.htm>.

- "World Bank in Zambia: Country Brief 2005-2006”, The World Bank Group.

- World Service Trust. “Zambia Country Report – Newspapers.” African Media Development Initiative: Zambia Context. BBC. 27 May 2007.<http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/trust/ pdf/AMDI/zambia/amdi_zambia7_newspapers.pdf>.

- “Zambia Mourns Wezi Kaunda.” BBC News. 9 November 1999. 11 June 2007 <http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/511321.stm>.

Reflections on "Lucy Banda Sichone (1954-1998): Voice of Conscience, Daughter of the Nation"

by Martha Sichone-Cameron

It would be almost 14 years before Mum would practice as a lawyer; I believe she only actually wrote and passed her bar exam in 1992 or thereabouts at which time she set up RAHAB Chambers - a Law Firm through which she would represent her clients.

I am not sure exactly what position she started with in the mines, but she ended up in a managerial position. She did obviously use her knowledge/skill both in her employment and personally, but never actually practiced.

I think it is also important to note why Kaunda was denied a permit in the first place because this was an issue that was close to Mum’s heart. After the first democratic and multi-party election that ousted Kaunda, he tried to run again because he was concerned that, amongst other things, Chiluba was ‘plundering’ the country (he privatized all government assets, including the copper mines). There was also a flood of foreign investors and the government was selling land that had belonged to people for generations. All of a sudden they were deemed squatters. Investors were also hiring people for new big, fancy super markets and paying them peanuts. As Chiluba was blocking UNIP/Kaunda’s permits, he was also altering the constitution by adding a citizenship clause to ensure that Kaunda, whose parents (like my grandparents) were immigrants from Malawi, would not be able to run. He almost tried to campaign for a third term of office. Mum’s mission that day was bigger than just the permit. It was the future of our civic rights as a country. She picked me up from work (I was on an internship at Alliance Française) and as usual a little crowd gathered around her, and she obliged them with an explanation.

This was not ‘foolhardy, at all. It was calculated and done with every confidence that she would not be hurt. She also got the intended response and reaction. It brought attention to a critical issue.

Mum never actually officially adopted any of the children that she “fostered”. This is typical of African culture. I know this mostly because of my fruitless attempts to keep one of the children that had come from an orphanage (Peter). I can also safely say that she also fostered more than three. Agatha was the first to be fostered as early as 1983. We also lived with about three cousins whom she raised –one of them, Hope, still uses Sichone as her maiden name. The other two have since passed.

Many others came through our home, some temporarily. Willie, Faith, and Peter were the last three who are referenced in this article. Willie was a street child who washed Mum’s car at the Northmead shopping center, close to where Mum’s offices were. He was unable to reform his street ways and he was eventually returned to his uncle. He died on the streets. Faith (picked from a drunken grandmother outside a downtown pub) was in the orphanage that I used to run until recently, when she was re-united with my mum’s sister’s family. Peter was adopted by an American family who we connected with and are in contact with. The same family also went on to literally foster my other biological brother.

My grandfather’s history had a lot to do with the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. We gathered a lot from stories that he and my grandmother lovingly told us (my cousins and I) over and over again in a crammed little living room in Buchi, Kamitondo where they lived. Beyond that I have only imagined and still believe I have an opportunity to establish his past because I know of his relatives and children who are still alive.

The Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland existed from 1953-63; Nyasaland, the smallest of the three countries, was un-developed industrially so was dependent to a far greater extent than the other two territories on its export of its labor. Most of its labor surplus was sent to Rhodesia, and, in particular, to the most active area, the Copper-belt, which at that time had huge reserves of copper ore that ranked the second richest in production in world. From stories, we established that it’s around about this time that my grandfather came and settled on the Copper-belt where he then met and married my grandmother. She already had five other children and had two with my grandfather: Lucy (1955) and Beth (1957).

Apparently he left a wife and children in Nyasaland, one of whom I met and still remain in contact with today.

Contrary to what a lot of people have thought I believe that my grandfather never worked a day in the actual copper mines but instead worked for a European (British) family - probably a high-ranking officer in the federal government - as a butler. My grandfather was immaculate in his dressing and kept his belongings and personal effects in such an orderly manner that everyone that knew him well can attest to. I believe he acquired this trait from his experience as a butler.

This could also be seen from his mannerisms (at meals, sense of humor, interpersonal relations), leadership qualities (exhibited in church), and habits (reading the newspapers, listening to the news). Also his passion for education caused my grandfather to go to great lengths to ensure that his daughters went to school, whereas my grandmother’s first three girls (still alive today) never completed schools and ended married with children at very young ages. Lucy, being the older and brighter one, did him proud. He loved my mother as did we, with a fierce passion! In an age when women’s going to school was frowned upon, my grandfather shaved his daughter’s heads and dressed them like boys so that they could attend classes. He personally took them to and from school on his bicycle. He also made them read newspapers at home.

This of course resulted in my mother becoming the breadwinner of the entire family. My grandmother's two sons were both black sheep (I know there is only supposed to be one) and literally showed back up when they were sick and/or dying. When it was my turn to go to school, my grandfather was all the more passionate. My mother being away at that time, he not only ensured that I went to school but monitored my progress as well. He would always reward me when I did well.

I think it’s unfair to call my grandmother a traditionalist in the ‘traditional’ sense of the word.

These are the early 60’s and a little bit of history would tell you what the education of Africans in general, never mind women, was like in that era.

Culturally all women were raised to look after homes and literally married off as soon as they came of age.

Despite this, my grandmother somehow managed to learn how to both read and write. In fact, she had a really beautiful hand. To the best of my recollection she was a student and/or worked for Mable Shaw.

Rare for their era, all three of my mum’s sisters had some level of education - albeit not very high. All three can read and write in the local language and barely in English. I believe she fully supported my mother’s education and always compared her favorably to the other women who gave up their education.

These were not mere allusions. My mother’s character was deeply rooted in her Christianity. Even her compassion and crusades for the less privileged ultimately had their foundations in the Bible. Both my grandparents were active Christians and raised their children so. All of my mother’s sisters are confirmed members of United Church of Zambia, the church that my grandparents faithfully attended and were leaders in, until their deaths. My mother became Catholic when she went to Fatima (the Secondary school that was run by catholic nuns) but I know that when she came to Oxford she must have also questioned/researched her faith judging by the kind of books that were on her bookshelf -including a lot of CS Lewis - and by the fact no one could compete with her personal knowledge of the Bible. She joined an evangelical church in the late 80’s and became a changed person. She gave this up probably because of some personal choices. She struggled with her faith later in her life but in her ailing months she re-established her faith. I am confident that my mother reconciled with and went and met her creator.

One of the stories that she loved to tell us about was how she was first treated when she got to Somerville. Apparently one of her tutors mistakenly believed that she was the daughter of the President of Malawi, Kamuzu Banda. She was invited to tea and given special attention until he realized that she was not “royalty”.

Quite honestly – with the standard of education we had in Zambia, I can understand how much she struggled and that it had to take someone as brilliant as her to succeed at such a prestigious university

“Ah-lah” was Mum’s signature “retort”! Blunt – yes, unapologetic – absolutely. And she went from Hall Matriarch to Zambia’s Matriarch - that was my mother. We did hear stories about “clueless people in Oxford”. I think it’s just hard for people to grasp what life, and what poverty, is really like if you have never seen it.

But we also heard very fond stories of friends that she left. I suspect they were also behind some of the amazing dishes (oxtail, stew, Shepherd’s pie and chicken curry to mention a few) that my mother would cook every Sunday. Rumor had it that she was not much of a cook before she went to the UK. I hope they forgive my mother for never getting in touch. Her life was totally turned upside down and I can imagine how hard it would have been to even communicate what she experienced

Even in the 70s (in Africa), you can tell (from pictures) that my parents were really, really in love. I believe that my father was my mother’s first love, because my grandparents, my grandfather especially, had always been very strict. To make his daughters go to school, he used to shave their heads and make them wear shorts and things so they would fit in and wouldn’t be frowned upon as girls. For high school, she went to an all-girls convent that was run by nuns. She would go from that to my grandfather’s well-guarded compound. When she went to college it was her first taste of independence. My dad was her first love. She got pregnant with me almost as soon as she went to college, and again from her you can see that these guys were really in love. She still honored her dad, she still finished her education, and she still went to Oxford, which I also believe had been the influence of my grandfather. She knew that it was really, really important in college. So I knew that my dad approved her going away. You can tell from their letters how he encouraged her and told her to keep strong in some of her early experiences.

I really believe that this relationship was cut short. I mean, not only did her husband die right as she was finishing Oxford, but she came home to a very cold reception. At the funeral she was not recognized as the widow, all of her things were taken away, and then all of a sudden she had these two kids to look after. I really believe that that made her bitter. She had this aggression about her in dealing with anybody. I don’t believe my mother was born that way, but I think it developed from her loss. Now that I’m older, now that I’m married, I cannot imagine leaving my husband at that early stage in our marriage. I cannot imagine raising two kids on my own. I cannot imagine doing that in our country at that time. When I came home from school, I knew how to wash my uniform - because we only had one uniform - and I would do my homework. For the longest time we didn’t even have a television, so she would come home, we would go over my homework, and then we would read the bible and pray before we went to sleep. It was done in a very religious way. We read a bible passage and she would ask me questions to see what I understood, what I felt, and she would get upset with me if I gave the wrong answer. She would get upset in the middle of a prayer if I kept repeating myself. I often wondered about that later—you know she did all of those things, religiously or whatever her reasons were, and they have really shaped my life.

I remember very clearly the day that my father died. My uncles used to make me little piggybanks, very simple ones, a wooden box with a hole in the top, which was filled with coins at that point. If you know anything about Zambia’s history, at some point our currency was so strong we were one and one with the pound. When I realized the value of these coins, I used to try to take them out of the box to use them for stuff, to use them for fritters and things. When my box was empty, I started stealing out of my (paternal) grandmother’s box. That fateful day, my dad was calling to me from a field behind our back yard and I thought I was in trouble, so I did not respond and I was hiding from him. My dad was trying to convince me to come, saying that I wasn't in trouble, that he just wanted to say bye -but I wouldn’t go to see him. I was laughing and running away, saying bye to him from a distance. That was the last time I saw him because he went off and got into a car accident and died.

Property grabbing was, and remains, a customary practice. It affected Lucy, deeply, but was not a surprise.

Being party cadres was fun actually. We had fun campaigning but it was awful when we lost as UNIP to MMD! I think she joined the party because she felt the new and ruling multi-party democratic government needed a viable opposition.

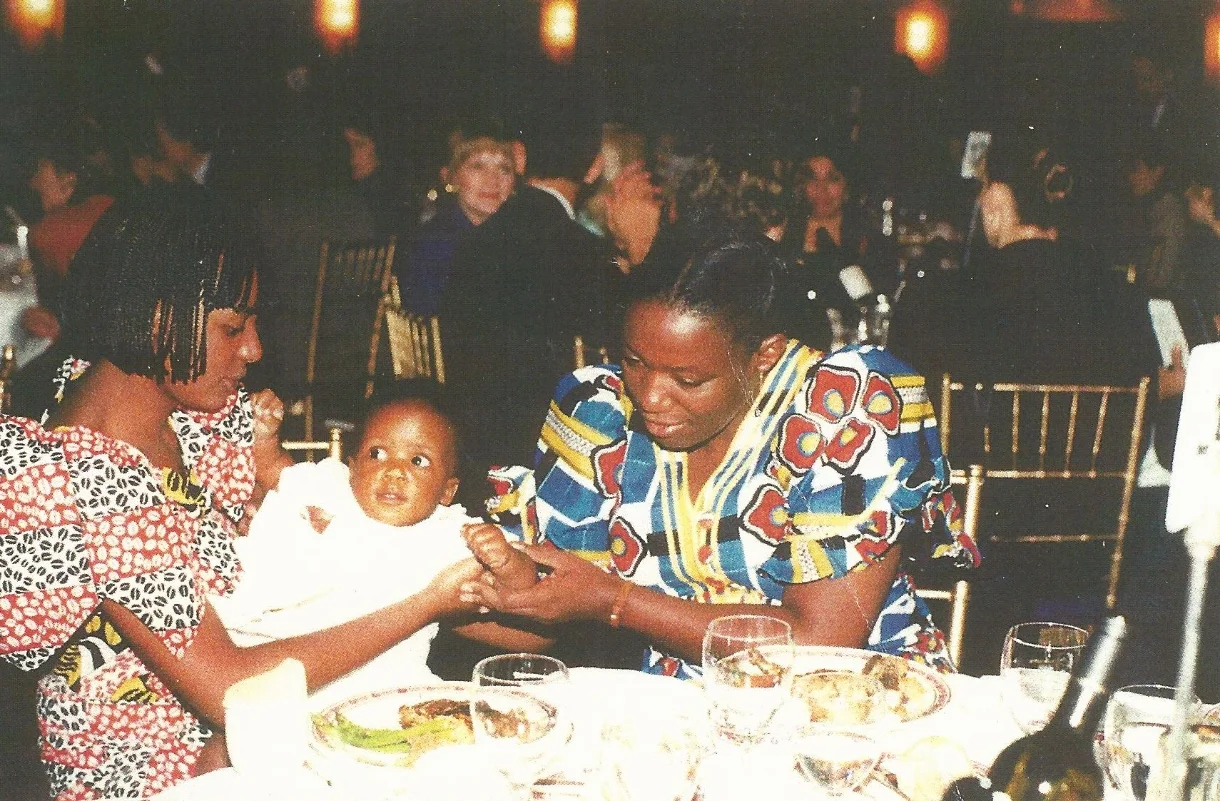

Photos of Lucy provided by Martha:

To this day, I defend my mother’s relationship with Kebby, however uncomfortable that time was for us. After my father’s death, my mother’s love life read like a tragic love story. In Zambia, I believe women who had extramarital affairs did so out of poverty or the desire of a better life from a man who could afford it. My mother did not need anything from Kebby; in fact he is the one who needed her to write his speeches and fund his campaign. But she was truly in love with him, and was a “fool for love” like everybody else who has ever been besotted. What is unfortunate about this is that people do not talk about it in the context of polygamy. Kebby’s tribe has an established culture of polygamy in which he was allowed to have more than one wife. In fact, most of the women who were well-known as his mistresses, were actually, in traditional sense, his wives. Most of the women and men who pointed fingers at my mother were hypocrites. My mother mourned deeply for Kebby privately and I witnessed and experienced how painful widowhood is for a second time.

As her children, we seem to have inherited a little bit of mum in different ways. My brother, Robert seems to be one who has inherited her literary skill and knack for political satire. He has a large following on Facebook and will probably be one to follow in mums footsteps, with a novel kind of civic education and awareness. My younger brother, Nathaniel seemed to have gotten the lion share of the brains; he is pursing graduate degree which is a reflection of Mums PPE combination at Oxford. He intends to be president of Zambia one day. I am the social justice person. The baby of the family is the socialite – mum’s true character of hospitality, togetherness and entertainment before it was marred by politics.

Was it defeat, or a wake-up call?

The first press conference for Zambia Civic Education Association was held in our backyard. She was so excited. But I know now it was such a step of faith. It was her and Elias Chipimo who is currently a presidential candidate in Zambia. He published his book a few years ago, and he dedicated a whole chapter of his experience with my late mother and the beginning of Zambia Civic. He was an Oxford grad, although not a Rhodes Scholar, and he had these high hopes and aspirations coming back to Zambia. He came back to work for a bank and had great aspirations but it all fell on deaf ears. Then he heard about my mother and “she blew his mind away” with her radical ambitions. Smart and ambitious - those were the kind of people that ended up surrounding her. Laura, Tina, and Austin - bright and gifted people who wanted to do something for their country. But it was quite a risk and a lot of excitement getting involved with my mother.

I have pictures of their first outreach as ZCEA, when they were going to these places that were, for lack of a better term, real ghetto places in the city. There was dirt and people were living in it, and she was saying, “These people need to be represented in government.”

Year in and year out they vote for this guy because when it’s time for elections, he would come and buy everyone beer and give them food and a piece of clothing and they would vote for him. But because of what was happening in those areas and the conditions were really terrible and she was going to these areas, we were worried for her.

The citizenship forum, a group of non-governmental organizations, really pushed for the constitutional review commission and of course mum took the reins. My mom made me and a lot my fellow student friends participate, she would say, “This is your country. This is your responsibility.” So the CRC was going around the country, and when they came to the University, I did go and make a petition regarding my right to becoming president (guess where that came from): the citizenship clause that targeted Kaunda would have disqualified me as well. I don’t think anyone really knew the specifics of what those petitions achieved. But then what does one do? People are apathetic – mostly due to ignorance—that was what civic education, and mums life’s work, was all about.

Talk about difficult to get to: I did accompany my mother on one trip in which we had to abandon our vehicle (all-wheel drive Toyota Land Cruiser) in order to cross a river in what was the remains of an old van that had to be pulled out of the river by several cows and bulls. She went to places where if , politicians were going for their “fake campaigns”, they would be taken via helicopter.

What is interesting is that Gen. Miyanda was later famously expelled, together with the 22 senior party officials in 2001, for opposing late President Frederick Chiluba's third presidential term bid. The third term bid was actively supported and led by the late President Michael Chilufya Sata. Who was then National Secretary and CEO of the MMD. At some point during that time, he must have remembered my mother.

That's interesting that at that time they could not see the world through her eyes because apparently now they do. After three failed governments they understand.

I find myself really grateful for having been raised by mother, because unlike some of my fellow graduates from Zambian universities very few seem to find it worthwhile to pursue social justice and defend basic human rights. And you don’t have to be a politician to do that. As a nation we are pretty apathetic- why else we would let our governments “get away with murder”. The murder of our nation?

The Courage in Journalism Award was awarded in response to her time as a fugitive referenced earlier in this article.

When she was a fugitive, it was pretty anticlimactic. She was at home, for the most part. She was not running around hiding. They knew exactly where she was. They would not let people into her house—we had armed guards, like I said, and the only way they were going to get her was if they came in with a warrant for her arrest. They had issued one for her and two editors of the paper, but it was a baseless warrant - a contempt of court and something else, I can’t remember. And they made an announcement that they were looking for her, but that nothing had happened to her. As soon as they made that announcement there was international pressure. And of course she won this award as well, basically for the same thing that had put a price on her head. It wasn’t as dramatic as you would think. She was a fugitive, she had resisted arrest. She said that if she had to go to prison, she would go with the baby, and the baby was really small at that time.

Then people started to tell her, “this is really serious, you have to leave your house, and go somewhere else”. It’s Africa but, they still have an intelligence movement that could figure out a way to get her out. We drove for four hours to my grandmother’s house. In Africa they still have road blocks and police stops on major highways for stopping people, for traffic violations. We must have gone through a police stop. My mother was a public face, and they had been told to look out for her, but when we passed through, they recognized her and they let her go. That’s how much people respected her. They knew they did stuff for the people and that this wasn’t fair. So the police would chat with her and let her go. We know that the threat was real and that it was imminent. I don’t want to down play that, but at the same time she was treated with respect. People came to her, and paid their respects to her, and they weren’t going to let the government take that away from her. That much I know. It wasn’t crazy at home. We didn’t need to disguise her or anything like that.

For us as her kids, nothing has rung louder and clearer than her tribute or “gift and lesson” which was her Courage in Journalism Acceptance speech delivered on November 18, 1996:

18th November 1996 was an important day for my Country, Zambia. It was the day appointed for our Presidential and General Elections in which I had both a personal and professional interest. I should have been home to witness and to monitor events as they unfolded. I made a deliberate decision to travel to the USA to receive this award on the basis that whatever happens in my country on 18th November 1996 will not suffer irreparable damage as a result of my absence.

The quest for Justice, the crusade for policies that will give access to the poor to medical facilities, clean water, shelter, basic food and proper nutrition for children under 5 years, the building of institutions that can look after orphans is a life time vocation which is not dependent on my being available on the 18th, I will go back to continue business as usual.

I have come here ladies and gentlemen, to receive this award because it is a once in a lifetime event. I was determined to come and receive this award in person because it is a gift and a lesson to my children.

This award is a gift to my children in recognition of all the terrors and uncertainties that they have had to endure because of the kind of vocation I have given to myself. My children were not consulted as to what I should do or not do. My children are not at liberty to remonstrate with me on the fact that my activities in the circumstances of our country put their lives at risk, abuse their rights to motherly care, abuse their right to life that if I was put away in prison or to a more permanent place like a grave, they would remain destitute orphans with neither a mother or father to provide food, shelter.

It is a gift to Martha, 22 years old, whoever since she was 6 years has lived with a big burden of the knowledge that as the eldest child the responsibility of bringing up her young brothers and sisters is hers--in my absence.

It's my gift to my son Muchemwa who at 16 years old, tries so hard and with childlike valor to be the man of the house.

It is my gift to Nena, who has had to learn to manage his fear of the dark on every night that I am absent from home.

It’s is my gift to Chambwa who at three months knew the terror and despair of being a fugitive from an unjust law. At three months, she found solace from the fear that was in me by desperately sucking two of her fingers in stoic silence. By the time she was seven months, she had learnt how to manage the terror, the despair the uncertainties that are inherent in my activities without the need of those fingers This gift recognises her achievement in stopping her finger sucking and taking on whatever comes her way which includes this trip around the world with 3 time zones, with courage, determination and good humour.

The award is also a lesson to my children that the human concepts of Justice, Love, Compassion, Courage and Fair play transcend colour, civilisations, boundaries.

A day before I travelled to the USA, I had an interview with an American woman whose organisation is working to establish a foundation to support independent media organisations in the Southern Africa Region. Upon being informed that I was travelling here to be given a gift for courage by IWMF, she was genuinely horrified at the prospect of my coming face to face with men and women in the American Media to whom my work, my beliefs, my children, my struggles for human dignity would not make sense. The only news from Africa which is capable of invoking interest amongst you here I was told was the Rwanda type of genocide, or the Ethiopian famine not for its human tragedy but for its commercial value.

The situation has been completely different, my children and myself have discovered that after all you are human beings Ladies and Gentlemen of the American Media. The fact that you men and women here can see, understand and recognise my small efforts to better our lot in a remote part of Africa called Zambia is a practical way of demonstrating to these children that their small acts of humanity, of courage, justice, compassion, their struggle to be human beings is not in vain, that indeed it is a worthwhile pursuit. And although the end result of this struggle is mostly persecution, imprisonment and death, the price in terms of one's humanity can never be too high.